Most conversations about AI assume autonomy is new.

That assumption is comforting. It suggests autonomy arrived with models and agents; and therefore can be constrained by AI policy, tooling, or oversight.

But autonomy did not arrive with AI.

It arrived quietly, years ago, through scale.

Long before agents, organisations had already become loosely coupled decision networks. Authority fragmented across teams, regions, platforms, and vendors. Context became partial by default. Decisions were made asynchronously, often without full visibility into downstream consequences. Action routinely preceded oversight, not because of failure, but because speed demanded it.

We adapted to this reality without naming it.

What we called empowerment, agility, or operating at scale was, in structural terms, autonomy: the ability for parts of a system to act independently, based on incomplete information, under local incentives.

AI did not create this condition.

It exposes it.

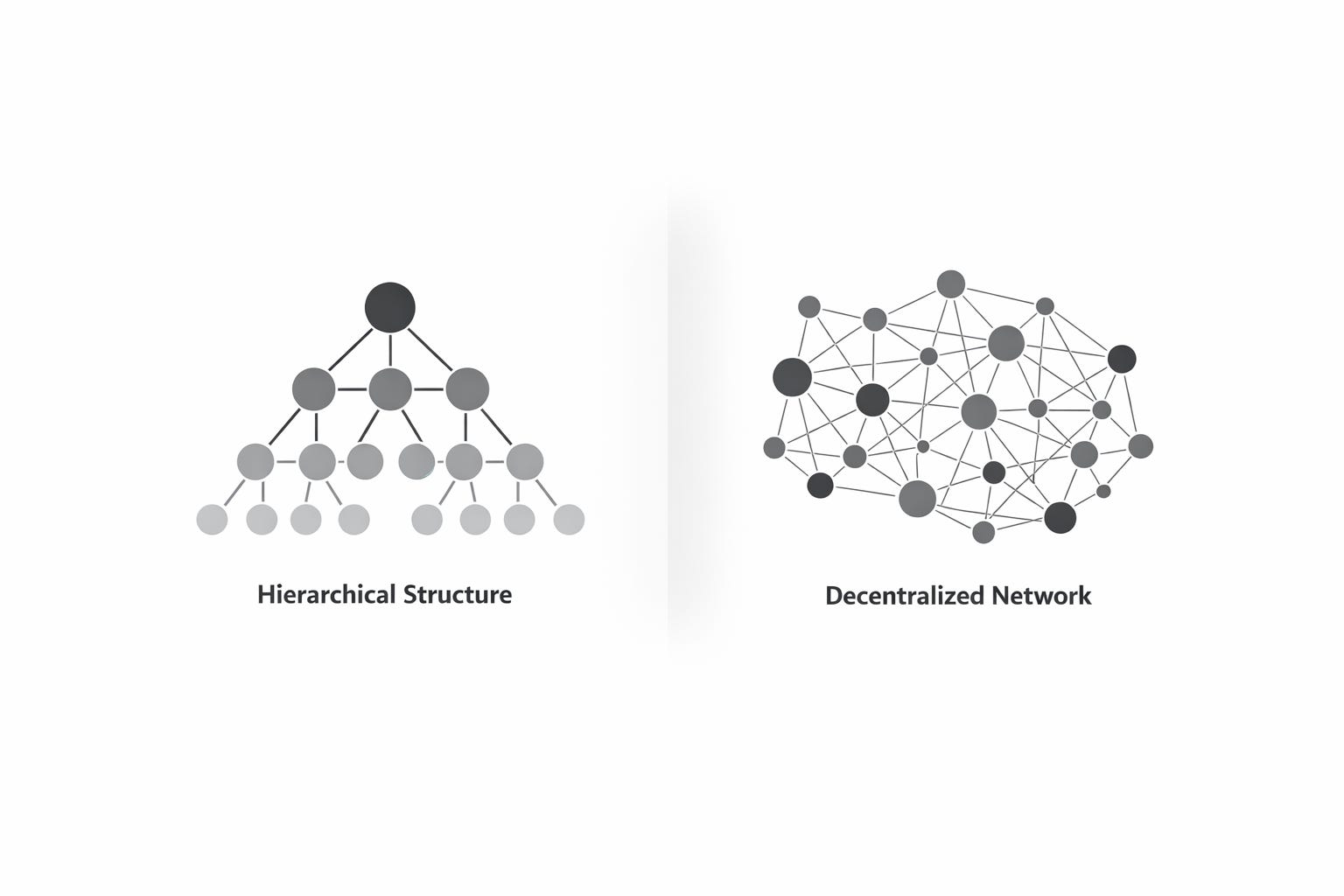

The illusion of hierarchy

Organisations still describe themselves as hierarchical. Org charts imply clear authority, escalation paths, and accountability. Governance frameworks assume control flows downward and outcomes flow upward.

In practice, this has not been true for some time.

As organisations scale, hierarchy becomes representational rather than operational. Decisions move faster than review cycles. Execution outpaces policy. Accountability becomes retrospective, not preventative. Control shifts from being structural to being performative.

This is not a failure of leadership or culture.

It is a failure of architecture.

Hierarchy assumes shared context, synchronous decision-making, and linear causality; conditions that no longer hold in modern systems. We responded to this mismatch not by redesigning structure, but by adding process: committees, approvals, human-in-the-loop checkpoints.

Each was intended to restore control.

Each quietly acknowledged it had already been lost.

Autonomy without architecture

Autonomy, when unacknowledged, becomes ungoverned.

Most organisations operate with high degrees of implicit autonomy and low degrees of explicit architectural constraint. Teams are free to act, but the system lacks mechanisms to arbitrate, bound, or reconcile those actions in real time.

Under low stress, this appears to work.

Under load, the cracks become visible.

Conflicting decisions. Cascading failures. Surprising emergent behavior. Not because individuals failed, but because the system provided no stable control surface through which decisions could be coordinated.

AI accelerates this exposure.

When decision-making becomes faster, cheaper, and more distributed, the absence of structure becomes impossible to ignore. What was once manageable through human intuition now exceeds cognitive and organisational limits.

The problem is not that AI systems act autonomously.

The problem is that we already were, without designing for it.

Why this matters now

It is tempting to treat this as a tooling problem. To believe better models, more observability, or stricter policy will restore control.

They won’t.

Control does not emerge from intention.

It emerges from architecture.

If autonomy is systemic, governance must be systemic too; designed into how decisions are made, constrained, and reconciled, rather than retrofitted through oversight after the fact.

This requires abandoning a comforting myth.

Autonomy didn’t arrive with AI.

It arrived when hierarchy stopped working.

And that failure, quiet, gradual, and largely unacknowledged, is what we need to examine next.

Next in the series: The Quiet Collapse of Hierarchy